Πηγαίνετε εκτός σύνδεσης με την εφαρμογή Player FM !

Episode 25: Making Up Cults!

Manage episode 371389409 series 2631359

Our guest for this episode is Austin Conrad, who last graced our podcast in episode 2, On the Road. Austin is the author of many things on the Jonstown Compendium, generally publishing under the “Akhelas” brand, while he is known as “Crel” on BRP Central, Discord, and social media.

Introductions

Austin is a contender for the most productive publisher on the Jonstown Compendium with his 24 issue Myth of the Month series that ran for the first two years of the Jonstown Compendium, culminating in the sizeable scenario booklet To Hunt A God.

Akhelas is the name of the setting Austin started writing in 2016 before the Jonstown Compendium even existed, and before he was even involved in Glorantha. The setting is inspired by Homeric epics and the tales of Herodotus, and especially Thucydides and the conflicts of city states.

The cosmology of Akhelas derives heavily from Platon’s Timeas, and the setting is kind of on the edge between Bronze Age and Classic Age. Little wonder Austin “took to Glorantha like a duck to water”.

When Austin is going to start publishing this animist city-state Bronze Age warfare stuff, he expects people to point to Glorantha as a parallel. Great minds…

Austin expects to self-publish his first novel maybe later this year, more likely next year.

Ludo mentions that Shawn and Peggy Carpenter have returned their publication Valley of Plenty, with new material added: extra detail, new cults, extra adventures. Like Austin, Shawn has announced a novel for next year.

To Hunt A God

According to Austin, To Hunt A God is a heroquest where your adventurers do the thing it says in the title.

Before we conclude this episode with this definitive statement, Austin expresses his sense of accomplishment after getting this book into print on demand. He urges everybody to sit down and publish their stuff in the community content program. More stuff is great, and sitting down with your own book is a spectacular experience. Getting it print-ready took Austin about a week of work and then six weeks of waiting.

To Hunt A God contains a new cult for players, Hrunda. Austin had the goal to provide a player cult that people would want to belong to. Another major section of the book is a temple site dedicated to Hrunda and a number of associate beast totem cults with their human and animal worshippers.

The second half of the book contains the adventure. It sets off with a religious festival attended by the player characters. We discuss the location of the temple and the Old Woods in relation to Esrolia (west of the Skyreach range, north of Longsiland, the easternmost outreach of the Arstola forest).

Austin calls out both similarities and differences with the Wild Temple in Beast Valley. The temple in the Old Woods is more modest in extent, concentrating all its important holy places in a small area.

Austin explains that the adventure originated from his RuneQuest Glorantha campaign situated in the city of Sylthi in Esrolia. We talk a bit about how this piece of Arstola is different from the rest of the forest, and where to find information.

Austin admits that he still needs to catch up listening to our podcast. Ludo is not sure he has his priorities straight.

Making Up Cults

Ludo elaborates on how cults are the defining difference between RuneQuest Glorantha and other fantasy games and settings, and how sooner or later every group or GM will leave the canonical selection of cults behind for their own special thing. Even with the upcoming publication of the Cults of RuneQuest books (“more cults than you need”) you will sooner or later find your own niche cult. Jörg points out that already the third adventure in the Colymar Adventure book gives the player characters a choice about how the deity of the backstory will turn out, showing the official endorsement of this practice. Ludo counters with the Quickstart adventure which will lead to some new cult activity if the players go for mostly non-violent solutions.

Austin confesses that he is a great fan of making up cults. GMs as well as player tend to buy in to their game by adding a personal touch. In mainstream D20 games people make their own character class. In RuneQuest set in Glorantha these are the cults. Austin talks about numerous cults and deities that he wrote up for his Esrolia game. Ludo teases that people might understand this as a backlog of upcoming books, but Austin quickly denies anything within calling distance. There was a reason he needed 18 months to finish To Hunt A God after having hit a hard start into 2022, and re-entering a project with a thousand pages of notes after such a break won’t produce results quickly. Austin compares his creative process to that guy who has a disassembled car project in the garage he religiously visits, only to drink a beer or two rather than put in some effort.

Austin also explains how him turning to a full time writing job means that people need to buy his books if they want the Esrolia project to proceed, as there will be fewer commissions outside of his Glorantha writing.

Inspired by the Red Book of Magic

The Red Book of Magic is the collection of all the Rune Spells and special Spirit Spells from the Cults Books (at least at the time of its publication back in 2020, when we naively thought that the Cults Books would be just around the corner). Because of the delay of the less typical cult write-ups, Austin states that a spell without a known cult has no obvious way to use it in your game: a collection of toys without giving you the instructions how to use them.

One spell that caught Austin’s attention (and affection) was Proteus, a spell that allows the caster to change their shape into a shape that they have devoured earlier. While owners of RQ3 Gods of Glorantha would be able to find that this is a Triolina spell, people without this long out-of-print supplement have no way to associate that spell with a cult or to make use of it. Austin saw the Movement Rune, originally owned by Larnste, the god of Change.

Austin complains that the river cults are “boring as hell”, which is why he gives the river cults in his area access to shape-shifting. Austin had a player whose thief character could shape-shift, and it was a disaster, and they had a great time.

In Austin’s version, the river cults would give their worshippers three shapes that they could acquire with Meld Form (an Enchantment which doesn’t cost POW). These forms were bull, ram, and crocodile (actually baby crocodile).

Austin suggests that use of this spell combo could make Hsunchen shape-shifting magic less overpriced, with a beast partner sensing their approaching death potentially volunteering to give their shape to a human partner.

In summary, if you want to give access to an orphaned spell, how do you fit it into the setting in a way that is kind of unusual and unexpected.

Ludo describes how playing the scenario that he later published as Bog Struggles the players got access to the spirit of the River Horse, It seems to be very common to encounter spirits or forgotten godlings whose magic may get accessible as a spirit cult.

It is a question “What do I get in return for joining this cult”, and Austin points out that this mind-set was typical for the ancient (and earlier) periods. Cult practices were of a transactional nature – I give you this cow and you stop messing up my harvest by sending (pr withholding) rain. Deities were powerful forces, but not role models, unlike in modern monotheism.

Ludo calls the deities selfish assholes who mess with people and stuff, make children with whatever and demand worship and adoration. Jörg compares the deities to service providers who need to be propitiated in order to get the necessary service. We go on talking about Orlanth as Comcast deep in Balazar… We talk about how you only get the right kind of lightning when within reach of at least one of the holy mountains.

Types of Cults

The RuneQuest rules recognize several layers of cults by importance as well as by the target entity.

Spirit Cults

Spirit cults are a place to start if you want to screw with cults. They found very naturally upon exposure of the adventurers to the cult entity.

Austin wonders whether spirit cults are regularly established via adventurer types or whether they may be started by ordinary folk in the setting of Glorantha.

Ludo posits that usually there will be a shaman nearby whose job it is to monitor spirits and to know how to deal with them, both to avoid arousing them and when player adventurers or unlucky NPCs have aroused them (creating scenario hooks).

Jörg has a different approach, with spirits of and in the household or on a ship etc. being interacted with by ordinary people – often propitiated, but also asked for boons or magic.

Austin talks about household spirits falling into Ernalda’s domain, and Ludo brings up ancestor worship as another form of personal relation to spirits. Austin expects non-adventurer people not founding spirit cults but initiating into existing ones (providing the necessary number of worshipers for shrines to work). E.g. a minor healing spirit able to provide Cure Disease who may temporarily attract a great following.

Mechanically, spirit cults are a way to give player adventurers that one spell they cannot get from their main cult but can’t live without. Austin compares them to prestige classes in certain D20 games. In RuneQuest, this ties into the Power economy: how much you put into Rune spells, how much into personal enchantments, or other uses.

Austin re-invents the existing Praxian spirit cult Lightning Boy (the local form of Orlanth Adventurous).

Austin talks about giving a spirit cult a special rune spell and maybe one or two common rune spells. In hindsight, his treatment of Hrunda in To Hunt A God may have been over-complicated by giving some but not all common rune spells.

For another example, a Naiad who grants Breath Air/Water might make that POW investment more attractive if her cult also gave Heal Wound as an alternative use for that rune point.

Cult entities of spirit cults tend to be fairly minor deities or big spirits. Ludo thinks of them as not big enough to have played a role in the Gods War.

With major cults, Ludo sees a lot more strings attached.

Jörg proposes spirit cults as shards of greater deities unavailable in the local pantheon, e.g. in Prax (Lightning Boy) or the Lunar Heartlands. Austin and Jörg riff about farmer magics.

Austin asks whether most spirit cults would be formed after accidental encounters with a spirit, or whether people went out of their way to find a spirit to worship for a certain purpose. Ludo and Jörg agree that encounters play a role, whether in a game or in stories. (There are cases of heroes bringing in spirit cults to serve their communities, like e.g. Balazar with Mralota).

Ludo argues that spirit cults are just the first phase of a regular cult, with most remaining at this size (or disappearing again) while others grow and grow until they qualify for temples and regular cult structures. Ludo can see how (a local form of) Yelmalio could start out as a spirit cult before attracting more than a few dozen worshippers.

Other people go on exploratory heroquests to bring back an entity filling their needs that may turn out to be just an aspect of a greater deity (or grow into one). Jörg uses the simile of people describing the elephant by touching one of its parts to describe how such explorers may not grasp the full extent and associations of a deity they have contacted. Even major cults cannot really embrace the entirety of their deity.

Propitiation is a major point in spirit cults, too – giving sacrifice just to an aspect to be left in peace.

People constructing cults and shaping cult entities are known, too. Most notorious were the God Learners, but they were hardly alone. Austin points out that there is no reliable systematic approach, things need to be messy. Jörg suggests another term of these partial worship, splinter cults.

Austin makes a difference between contacting a tree spirit that exists within Time from contacting a God Time entity or partial entity like Aldrya. Austin also warns us not to delve too deep into the differences between God Time and Time…

Hero Cults

Austin starts with the observation that a hero cult is like a spirit cult, using the same mechanic. Ludo and Jörg point out that the difference lies mainly in the cult entity, as a worshipped cult hero may still be alive. Ludo even suggests that the entity can be one of the player characters.

Austin observes that it can be very fun to be worshipped, because then you get special powers. Jörg sees also a ball-and-chain aspect of being worshipped, as the cult entity gets pulled into the same role again and again, will he or nil he. Ludo asks whether that is more your echo in the God Plane, but Jörg claims that your echo and ego align over time. Ludo asks to expand this, so he can throw more shenanigans at his players (possibly referring to Austin here).

Ludo lays out the rules side of the deal. Your hero goes on a heroquest and obtains a heroquest ability and some hero points to activate it. Your hero then regains the hero points by being worshipped, and the worshipper in turn gain access to (a toned down variant of) the heroquest ability as a rune spell.

Jörg names Hofstaring Treeleaper as his go-to character for a hero with a cult. Hofstaring is worshipped among the Culbrea tribe, with some getting the tree-leaping rune spell. If Hofstaring was still alive, he would easily be challenged to jump the next impossible tree.

Austin prefers Jar-eel as his example (she has that effect on people who encounter her). If you were facing Jar-eel and you had a feat that allows your axe to do double damage against Lunes (Red Moon elementals), that feat would carry over into a vulnerability for the woman who is essentially the Red Goddess walking on (Gloranthan) Earth. She also has to fulfill commitments beyond what other initiates or rune masters have to.

Jeff Richard wrote a while ago that a capital H Hero will have transgressed against their cult, too. Ludo argues that that is the way to bring progress to the cult, with ultimately the hero cult feat/Rune spell becoming a mainstream cult spell.

Ludo asks how to play out this integration into the wider cult in a game without doing something like a three year break with some charisma rolls to convince 1D6 temples to adopt your method. Jörg suggests that this may happen in the face of cataclysm when the hero’s feat becomes crucial in averting a bad fate. With the Hero Wars basically consisting of a whole series of upcoming cataclysms, no shortage there (and no big deal if the GM adds another one). Or, as Ludo puts it, there are no Hero Wars, just min-maxing players with delusion of greatness. Austin feels called out by this.

Subcults

Subcults are a way to add a new aspect to a cult entity. One thing Ludo likes about Greek mythology is that there were many places where a special role was attached to an otherwise well known deity. There was a temple of Zeus Flyswatter (Zeus Apomyios) in a great collection of temples where all manner of animal sacrifice went on, which naturally attracted flies to the slaughter.

Jörg posits a different approach: whenever you write a new myth about a deity (or otherwise cult entity), you create a new subcult. Ludo thinks that’s the business of hero cults, but Austin points out that many hero cults are basically subcults of the existing cult of their hero. There are hero cults outside of existing cult structures, with Harrek the Berserk as a case study. Austin paraphrases Jeff Richard that Harrek gets worship for the same reason Malia does: “Oh please, Harrek, don’t come this way!”

Ludo makes Jar-eel the poster girl for the opposite way, a hero fully integrated into her deity’s cult. We discuss poster girls in the sense of Carry Fisher’s Princess Leia bondage image being worshipped by young boys in (or rather from) the seventies and eighties.

Austin really likes these distinctions to be messy and ambiguous. While some of the introductory material could be more straightforward, the ambiguity is what makes Glorantha (or mythology in general) fun to play around with. “Maybe that elephant has wings.”

Austin has the revelation that the entirety of the Gods War was just a dog toy. Ludo is sure that there was a God Learner theory supporting that, and Jörg locates that in the library of the sunk Trickster library in Slontos.

Jörg offers another distinction between hero cult and subcult – when did the myth (or introduction of the feat) happen, in God Time, or as a heroic effort within History?

Ludo fleshes this out – you can come back from the discovery of how to leap trees saying “look at me, I am awesome because now I can leap over trees, so worship me!”, or you can come back saying “I went to the God Time and met this kinsman of Orlanth called Bob who taught me to leap trees, so everybody worship Bob!” Hero cults are for egomaniacs, while subcults are founded by true devotees. Or the difference between Rune Lords and Rune Priests, as Jörg puts it.

Syncretism rears its ugly head: You encounter a deity which shares certain angles with your own, like e.g. being the cruel god at the Hill of Gold, chaining Orlanth to Shargash (or the Fronelan form Vorthan) and ultimately Zorak Zoran, possibly bringing in shared magic.

Austin gives an example of how the Death Wielder feat can do such heroic mis-identification that nonetheless can give access to powers.

Ludo takes Heler as the example – this could be the personification of the rain as a bona fide deity, or it could be just the name for Orlanth’s power to make it rain without any intrinsic contradiction. Vinga can be a daughter of Orlanth or just a female aspect of Orlanth. It compares to dedicating yourself only to part of the cult, like a Star Trek fan only ever watching the original series, and not the entirety of the franchise.

We conclude that you should not ever involve yourself with a fandom. And no, we aren’t fans, we are devoting ourselves to serious study of Glorantha. Ahem.

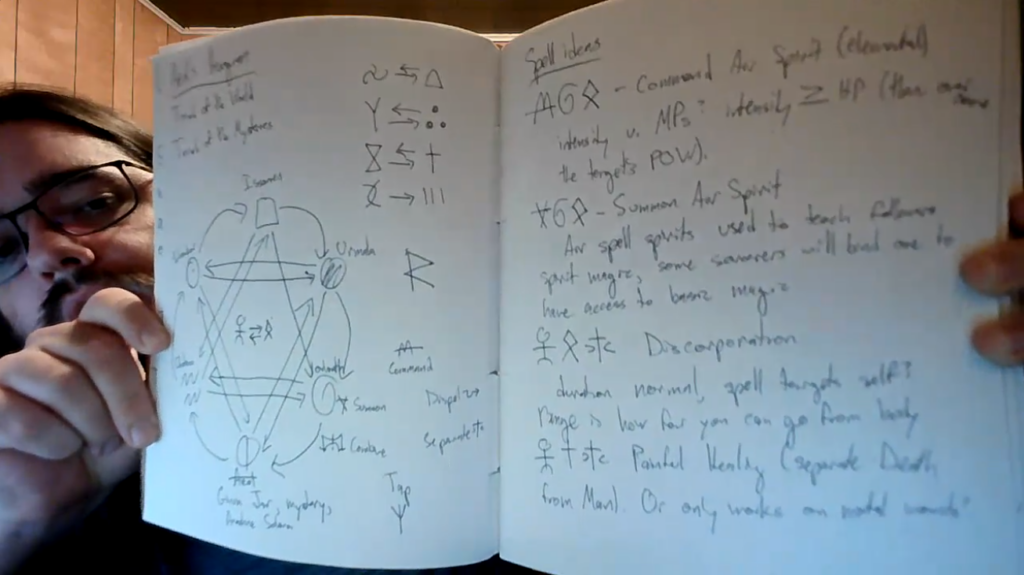

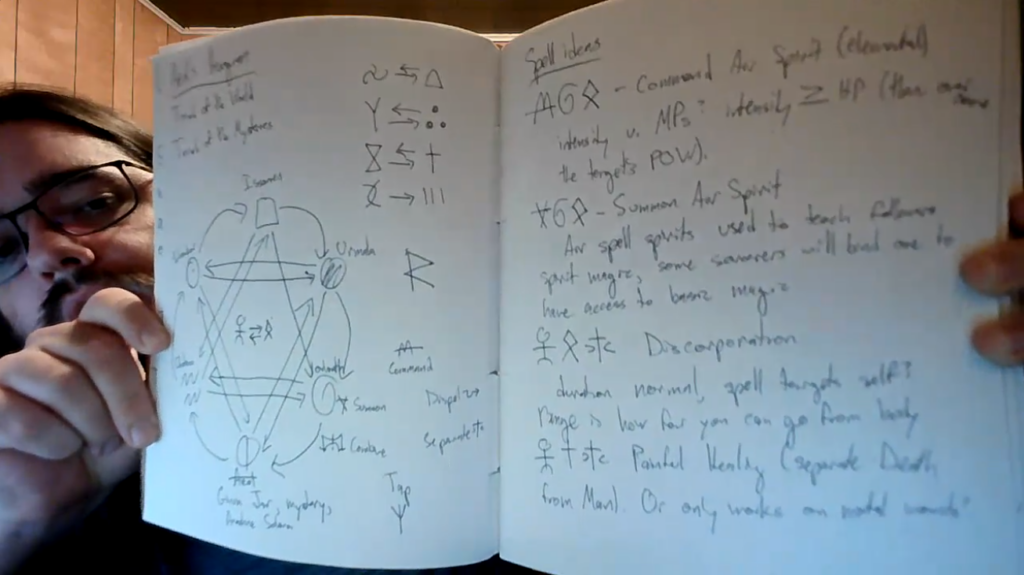

Jörg reminisces about dipping his own feet in Gloranthan fan-subcreation tackling the weird henotheism of Malkioni worshipping regular deities, like that Aeolian sect in Heortland. This triggers Austin to bring up his deranged scribble journal. Austin (too) spent three days rambling about Aeolian sorcery in his notes.

The Aeolians sit in southern Heortland, between Orlanthi Heortland (Hendrikiland) and God Forgot, a land of atheist sorcerers who either are Brithini or think they are, imitating their ways.

Austin’s deranged ramblings for Aeolian sorcery (which may never see the light of day any more than the picture above) have new relationships between runes, or assign elements to deities which aren’t apparent anywhere else. The premise is that the Monomyth could be very wrong and the magic still works, which is made possible by having the sorcery element which doesn’t rely on the warranty of your rune magic. Sorcery gives you the tools to jailbreak your phone, it is really good at it. Sorcery also allows you to infer and use the antithesis of a rune you mastered.

Regardless whether he will use it in publication or not, what Austin found out from this exercise is that if you don’t play with the cults but with the runes you are getting different results in your sub-creation.

Austin feels that the Monomyth as presented over-emphasizes the role of the elements, He plays through an experiment where all the Lightbringer deities are purely made up of power runes, including Orlanth.

Things get too messy to transcribe, or to count potential Nysalorean riddles.

Austin rambles about Entekos the still Air Goddess being the wife of Orlanth, challenging many magical preconceptions.

Jörg rambles about Orlanth possibly not being born a storm god but becoming the Storm King through his teenage hero journey through the Gods War.

Austin riffs on how the sorcerous ability to infer the antithesis of a power might influence a henotheist offshoot of a religion.

Jörg mentions his own first steps toying with the Aeolians.

Austin talks about approaching cults as a game tool rather than a setting feature and what would be interesting to mechanically play around with. Engizi is a case study of what Austin doesn’t like very much in the core rules book, there is little to incite a player to follow this deity.

As a counter-example, Austin cites Brian Duguid’s cult of Mee Vorala in his recent The Voralans offering on the Jonstown Compendium (Brian was our guest in episode 17, by the way) Austin could see himself as a troll mushroom farmer with access to cool alchemical toys and unexpected magics. “It is a really nice blend of inventive mythology and actual I could play this.”

Jörg points out that his tinkering with the Aeolians was accompanying his first time GMing RuneQuest in Glorantha after years of experience GMing RQ in his own settings, making actual play with the rules system a powerful motivation at the time, too.

Rune Cults

Austin’s Cult of Hrundra in To Hunt A God is an example of this.

For Austin, every fun idea doesn’t stand alone but blurs into a melange. One idea behind it was an illusion-focused knowledge god would be interesting. While Hrundra turned out not to be this, this was one of the starting points. Hrundra’s monkey shape was inspired by Thoth, the Egyptian baboon-headed god of knowledge (Besides the baboon head, Thoth is also often depicted with an Ibis head, in case you were wondering how you misremembered.) Austin has a blue statue of a baboon apparently dedicated to Thoth which gave him the notion of the blue monkeys. The actual imagery for Hrundra’s species came from howler monkeys from South America. Austin likes to take not one but maybe sixteen different influences to create a new one.

To Hunt A God was intended as the big finale of Austin’s Monster of the Month series, where he wanted to throw this big cool monster into the path of the players to deal with.

Ludo asks why Hrundra was designed as a stand-alone deity rather than like Gouger, the Ernaldan cult monster boar sent as a punisher at the start of Time. Austin basically just wanted to do it this way. Really wanting to do it is part of the fun to create things this way.

Ludo asks about pitfalls, dangers etc. to look out for. Austin remembers that writing the cult was a fairly easy exercise, as he wrote the first half of the publication in about a month. The cult was following a lot of standard structures, including Campbell’s Hero’s Journey, Eliade’s shamanism, and of course the full RuneQuest cult write-up outline originating in Cults of Prax.

Playing a campaign around Sylthy in Esrolia at the time, Austin also thought how the cult would be perceived outside of the forest it protected. In his game, the Temple of the Bones is the only such cult centre in the region for a lot of the gods of the wilds, including Yinkin who does receive associate worship in many Orlanth shrines but doesn’t have a full (minor) temple anywhere except maybe in Nochet.

Jörg asks about Kipling’s Jungle Book as an influence on the Temple of Bones with its assortment of wild deities – bear, snake, large feline, monkeys…

When thinking about Hrundra, Austin’s goal was cool fun cults, with more power than a cult of this size would really earn from a pure setting perspective. Jörg points out that this is balanced by the very hard geographical limit of the cult’s influence, but Austin just likes to make the setting more “gonzo” or “Bollywood”. Austin points to the gritty and personal style on the cover of the Starter Set while the setting also allowing over-the-top magics (like the Dragonrise image in the interior of the Starter Set).

Ludo talks about a scale in the fandom of Glorantha, with some making it a very archaeological world with everyday items like looms and farming, all the way to the completely gonzo scenarios by Sandy Petersen or Nick Brooke (The Black Spear, Crimson King). Both Austin and Jörg claim both ends of the spectrum for themselves, with Austin giving an example he read about a change in Mesopotamian plowing techniques documented in cuneiform tablets led to seeds being sown deeper into the soil, leading to greater crops, leading to population growth and a period of increased warfare.

Ludo asks how runic interactions influence Austin’s writing or design. Austin regards the Form and Element Runes as nouns and the Power Runes as verbs, and the antagonism of the Power Runes plays a greater role in his design. Austin talks about how the rune dice which allow you to roll a situative rune are great props for framing a scene. Austin reads and interprets the runes, possibly more for his deranged scribbles stage of collecting ideas than for his more structured writing process.

Austin comes back to how Hrunda has lost any connection to the initial knowledge god concept, having turned into a trickster scape-goaty thing. Austin likes how Hrunda fails to fit neatly into any of these boxes, if he did he would be too mono-mythy for Austin’s tastes.

Jörg points out that Hrunda also does this by having a significant shamanic element to his theist cult. Austin emphasizes the shamanic nature of the cult and mentions how that makes getting the support for a temple unlikely. That is why he came up with the Temple of the Bones as a joint shamanic worship site where small followings of shamans of different wild gods would help one another out as lay worshippers boosting the size of the holy place.

Jörg mentions the animal worshippers of Hrunda (the non-sentient of the bluepaws monkeys) whose attendance also boosts the site beyond normal temple restrictions.

One of the images inspiring Austin was swarms of monkeys attacking people in the streets of very urban cities in India like sea-gulls. So Austin thought to throw a bunch of monkeys into urban Esrolia, as a major pain in the butt, and some of them talk.

This worship by animals is a trick first published for the Cult of Zola Fel with its intelligent and non-intelligent fish worshippers. Austin saw that and thought this should be more widespread than just one river god in the middle of nowhere.

Austin also emphasizes that the bear (Odayla) worship at the Temple of Bones is very different from the Rathori Hsunchen ways, and has no (ancestral) relationship.

Cool Toys for Players

Ludo asks for a rather specific cool toy like e.g. turtle shell powers that a player might ask for.

Austin talks about several ways to handle this. In the case of Hrunda the cult was there first, and then the toys came up when muddling around the different stories that resulted from that. Most of his key magic is stuff Austin made up following the pattern of Yinkin (which in turn follow the pattern of the Hsunchen entities while avoiding the shapeshifting aspect).

Austin remembers thinking about writing a short cult creation guide when the Red Book of Magic first came out, but other commitments and doubts about how it would be received resulted in about ten thousand words being shelved indeterminately. Ludo suggests publishing such notes as the Conrad Library, while Jörg asks for the Akhelas manifests. If you ever see “Volume 2 – The Great Re-Ascent of Bullshit” in print, Ludo suggested it here first.

Taking the RQ2 Rune Power concept backwards, Austin posits that if you see a bunch of spells with shared runes, you can create a cult from that retrospectively.

For an example cult of Fire and Death, Austin talks about taking five or six spells, say True Spear, Produce Light, Earthwarm and maybe two or three others. One of the spells is exciting, three are okay and useful, and then there is your equivalent of Cloud Call which is mythically significant but dull as hell. You muddle these together, and then you ask what are the stories that led to those spells.

So if you have a fire god with True Spear, how did he win his spear? Was he born with it, did he tear his own rib out to get a spear, did he climb a tall mountain and use its peak as a point of his spear, did he chop a tree down and now carries a spear but his cult is hated by elves, was he born as a spear and then became a man – weird random ideas that you can draw from.

A rune spell in Austin’s mind is really an embodiment of the myth. You are throwing a story at somebody and it blows up in their face.

So if you want to have Proteus for a spirit cult, you might make it slightly malignant, to have to keep the magic you need to acquire a new form regularly (Austin initially suggested once a season, but then ruddered back to once a year). It is a way to have the really cool toys, but requiring that you cast Sanctify or similar regularly is going to cost you. Reasons to adventure, reasons to do stuff.

Hrunda has the story about stealing fruit, as a consequence initiates cannot let each other starve, and as a shaman or rune lord your are not even allowed to pay for food, you have to be offered it for free, steal it, or grow it yourself,

As a last word on creating cults: Just do it. You will make mistakes, and you will learn from these.

Austin talks about the upcoming volume on Mythology in the Cults of RuneQuest series and how he fears it might contaminate his creativity. Jorg speculates about some of the contents, with many old acquaintances appearing, and absences being more glaring than inclusions.

Closing Statements

Austin’s stuff can be found on the Jonstown Compendium. He also has a website, where he publishes his weekly blog, Glorantha stuff, backstory for his original world, a play report for Six Seasons in Sartar, a review of The Design Mechanism’s Mythic Babylon, trying soloquest rules and solo gaming, etc.

Austin’s most recent offerings on the Jonstown Compendium are the print version of To Hunt A God and the PDF of The Queen’s Star, a site-based adventure where you go to the Cinder Pits in Colymar lands, mucking around with fallen sky gods trying to convince them to let someone go.

Ludo takes the occasion to promote some of the stuff he has recently participated in on the Jonstown Compendium: Veins of Discord by Finmirage where he did most of the illustrations and the layout, a few drawings in The Voralans by Brian Duguid, the cover for To Hunt a God, and also one little illustration in The Queen’s Star. Ludo also teases Jörg about his still not upcoming work on Ludoch (and fisherfolk) in the Choralinthor Bay.

The God Learners on Holiday

On a more general note, the next episode of the podcast is scheduled for early September, so please hold the line (And that’s the last telecommunication simile in this transcript, too.)

Any delays in releasing this episode are Jörg’s fault for being late with the transcript.

62 επεισόδια

Manage episode 371389409 series 2631359

Our guest for this episode is Austin Conrad, who last graced our podcast in episode 2, On the Road. Austin is the author of many things on the Jonstown Compendium, generally publishing under the “Akhelas” brand, while he is known as “Crel” on BRP Central, Discord, and social media.

Introductions

Austin is a contender for the most productive publisher on the Jonstown Compendium with his 24 issue Myth of the Month series that ran for the first two years of the Jonstown Compendium, culminating in the sizeable scenario booklet To Hunt A God.

Akhelas is the name of the setting Austin started writing in 2016 before the Jonstown Compendium even existed, and before he was even involved in Glorantha. The setting is inspired by Homeric epics and the tales of Herodotus, and especially Thucydides and the conflicts of city states.

The cosmology of Akhelas derives heavily from Platon’s Timeas, and the setting is kind of on the edge between Bronze Age and Classic Age. Little wonder Austin “took to Glorantha like a duck to water”.

When Austin is going to start publishing this animist city-state Bronze Age warfare stuff, he expects people to point to Glorantha as a parallel. Great minds…

Austin expects to self-publish his first novel maybe later this year, more likely next year.

Ludo mentions that Shawn and Peggy Carpenter have returned their publication Valley of Plenty, with new material added: extra detail, new cults, extra adventures. Like Austin, Shawn has announced a novel for next year.

To Hunt A God

According to Austin, To Hunt A God is a heroquest where your adventurers do the thing it says in the title.

Before we conclude this episode with this definitive statement, Austin expresses his sense of accomplishment after getting this book into print on demand. He urges everybody to sit down and publish their stuff in the community content program. More stuff is great, and sitting down with your own book is a spectacular experience. Getting it print-ready took Austin about a week of work and then six weeks of waiting.

To Hunt A God contains a new cult for players, Hrunda. Austin had the goal to provide a player cult that people would want to belong to. Another major section of the book is a temple site dedicated to Hrunda and a number of associate beast totem cults with their human and animal worshippers.

The second half of the book contains the adventure. It sets off with a religious festival attended by the player characters. We discuss the location of the temple and the Old Woods in relation to Esrolia (west of the Skyreach range, north of Longsiland, the easternmost outreach of the Arstola forest).

Austin calls out both similarities and differences with the Wild Temple in Beast Valley. The temple in the Old Woods is more modest in extent, concentrating all its important holy places in a small area.

Austin explains that the adventure originated from his RuneQuest Glorantha campaign situated in the city of Sylthi in Esrolia. We talk a bit about how this piece of Arstola is different from the rest of the forest, and where to find information.

Austin admits that he still needs to catch up listening to our podcast. Ludo is not sure he has his priorities straight.

Making Up Cults

Ludo elaborates on how cults are the defining difference between RuneQuest Glorantha and other fantasy games and settings, and how sooner or later every group or GM will leave the canonical selection of cults behind for their own special thing. Even with the upcoming publication of the Cults of RuneQuest books (“more cults than you need”) you will sooner or later find your own niche cult. Jörg points out that already the third adventure in the Colymar Adventure book gives the player characters a choice about how the deity of the backstory will turn out, showing the official endorsement of this practice. Ludo counters with the Quickstart adventure which will lead to some new cult activity if the players go for mostly non-violent solutions.

Austin confesses that he is a great fan of making up cults. GMs as well as player tend to buy in to their game by adding a personal touch. In mainstream D20 games people make their own character class. In RuneQuest set in Glorantha these are the cults. Austin talks about numerous cults and deities that he wrote up for his Esrolia game. Ludo teases that people might understand this as a backlog of upcoming books, but Austin quickly denies anything within calling distance. There was a reason he needed 18 months to finish To Hunt A God after having hit a hard start into 2022, and re-entering a project with a thousand pages of notes after such a break won’t produce results quickly. Austin compares his creative process to that guy who has a disassembled car project in the garage he religiously visits, only to drink a beer or two rather than put in some effort.

Austin also explains how him turning to a full time writing job means that people need to buy his books if they want the Esrolia project to proceed, as there will be fewer commissions outside of his Glorantha writing.

Inspired by the Red Book of Magic

The Red Book of Magic is the collection of all the Rune Spells and special Spirit Spells from the Cults Books (at least at the time of its publication back in 2020, when we naively thought that the Cults Books would be just around the corner). Because of the delay of the less typical cult write-ups, Austin states that a spell without a known cult has no obvious way to use it in your game: a collection of toys without giving you the instructions how to use them.

One spell that caught Austin’s attention (and affection) was Proteus, a spell that allows the caster to change their shape into a shape that they have devoured earlier. While owners of RQ3 Gods of Glorantha would be able to find that this is a Triolina spell, people without this long out-of-print supplement have no way to associate that spell with a cult or to make use of it. Austin saw the Movement Rune, originally owned by Larnste, the god of Change.

Austin complains that the river cults are “boring as hell”, which is why he gives the river cults in his area access to shape-shifting. Austin had a player whose thief character could shape-shift, and it was a disaster, and they had a great time.

In Austin’s version, the river cults would give their worshippers three shapes that they could acquire with Meld Form (an Enchantment which doesn’t cost POW). These forms were bull, ram, and crocodile (actually baby crocodile).

Austin suggests that use of this spell combo could make Hsunchen shape-shifting magic less overpriced, with a beast partner sensing their approaching death potentially volunteering to give their shape to a human partner.

In summary, if you want to give access to an orphaned spell, how do you fit it into the setting in a way that is kind of unusual and unexpected.

Ludo describes how playing the scenario that he later published as Bog Struggles the players got access to the spirit of the River Horse, It seems to be very common to encounter spirits or forgotten godlings whose magic may get accessible as a spirit cult.

It is a question “What do I get in return for joining this cult”, and Austin points out that this mind-set was typical for the ancient (and earlier) periods. Cult practices were of a transactional nature – I give you this cow and you stop messing up my harvest by sending (pr withholding) rain. Deities were powerful forces, but not role models, unlike in modern monotheism.

Ludo calls the deities selfish assholes who mess with people and stuff, make children with whatever and demand worship and adoration. Jörg compares the deities to service providers who need to be propitiated in order to get the necessary service. We go on talking about Orlanth as Comcast deep in Balazar… We talk about how you only get the right kind of lightning when within reach of at least one of the holy mountains.

Types of Cults

The RuneQuest rules recognize several layers of cults by importance as well as by the target entity.

Spirit Cults

Spirit cults are a place to start if you want to screw with cults. They found very naturally upon exposure of the adventurers to the cult entity.

Austin wonders whether spirit cults are regularly established via adventurer types or whether they may be started by ordinary folk in the setting of Glorantha.

Ludo posits that usually there will be a shaman nearby whose job it is to monitor spirits and to know how to deal with them, both to avoid arousing them and when player adventurers or unlucky NPCs have aroused them (creating scenario hooks).

Jörg has a different approach, with spirits of and in the household or on a ship etc. being interacted with by ordinary people – often propitiated, but also asked for boons or magic.

Austin talks about household spirits falling into Ernalda’s domain, and Ludo brings up ancestor worship as another form of personal relation to spirits. Austin expects non-adventurer people not founding spirit cults but initiating into existing ones (providing the necessary number of worshipers for shrines to work). E.g. a minor healing spirit able to provide Cure Disease who may temporarily attract a great following.

Mechanically, spirit cults are a way to give player adventurers that one spell they cannot get from their main cult but can’t live without. Austin compares them to prestige classes in certain D20 games. In RuneQuest, this ties into the Power economy: how much you put into Rune spells, how much into personal enchantments, or other uses.

Austin re-invents the existing Praxian spirit cult Lightning Boy (the local form of Orlanth Adventurous).

Austin talks about giving a spirit cult a special rune spell and maybe one or two common rune spells. In hindsight, his treatment of Hrunda in To Hunt A God may have been over-complicated by giving some but not all common rune spells.

For another example, a Naiad who grants Breath Air/Water might make that POW investment more attractive if her cult also gave Heal Wound as an alternative use for that rune point.

Cult entities of spirit cults tend to be fairly minor deities or big spirits. Ludo thinks of them as not big enough to have played a role in the Gods War.

With major cults, Ludo sees a lot more strings attached.

Jörg proposes spirit cults as shards of greater deities unavailable in the local pantheon, e.g. in Prax (Lightning Boy) or the Lunar Heartlands. Austin and Jörg riff about farmer magics.

Austin asks whether most spirit cults would be formed after accidental encounters with a spirit, or whether people went out of their way to find a spirit to worship for a certain purpose. Ludo and Jörg agree that encounters play a role, whether in a game or in stories. (There are cases of heroes bringing in spirit cults to serve their communities, like e.g. Balazar with Mralota).

Ludo argues that spirit cults are just the first phase of a regular cult, with most remaining at this size (or disappearing again) while others grow and grow until they qualify for temples and regular cult structures. Ludo can see how (a local form of) Yelmalio could start out as a spirit cult before attracting more than a few dozen worshippers.

Other people go on exploratory heroquests to bring back an entity filling their needs that may turn out to be just an aspect of a greater deity (or grow into one). Jörg uses the simile of people describing the elephant by touching one of its parts to describe how such explorers may not grasp the full extent and associations of a deity they have contacted. Even major cults cannot really embrace the entirety of their deity.

Propitiation is a major point in spirit cults, too – giving sacrifice just to an aspect to be left in peace.

People constructing cults and shaping cult entities are known, too. Most notorious were the God Learners, but they were hardly alone. Austin points out that there is no reliable systematic approach, things need to be messy. Jörg suggests another term of these partial worship, splinter cults.

Austin makes a difference between contacting a tree spirit that exists within Time from contacting a God Time entity or partial entity like Aldrya. Austin also warns us not to delve too deep into the differences between God Time and Time…

Hero Cults

Austin starts with the observation that a hero cult is like a spirit cult, using the same mechanic. Ludo and Jörg point out that the difference lies mainly in the cult entity, as a worshipped cult hero may still be alive. Ludo even suggests that the entity can be one of the player characters.

Austin observes that it can be very fun to be worshipped, because then you get special powers. Jörg sees also a ball-and-chain aspect of being worshipped, as the cult entity gets pulled into the same role again and again, will he or nil he. Ludo asks whether that is more your echo in the God Plane, but Jörg claims that your echo and ego align over time. Ludo asks to expand this, so he can throw more shenanigans at his players (possibly referring to Austin here).

Ludo lays out the rules side of the deal. Your hero goes on a heroquest and obtains a heroquest ability and some hero points to activate it. Your hero then regains the hero points by being worshipped, and the worshipper in turn gain access to (a toned down variant of) the heroquest ability as a rune spell.

Jörg names Hofstaring Treeleaper as his go-to character for a hero with a cult. Hofstaring is worshipped among the Culbrea tribe, with some getting the tree-leaping rune spell. If Hofstaring was still alive, he would easily be challenged to jump the next impossible tree.

Austin prefers Jar-eel as his example (she has that effect on people who encounter her). If you were facing Jar-eel and you had a feat that allows your axe to do double damage against Lunes (Red Moon elementals), that feat would carry over into a vulnerability for the woman who is essentially the Red Goddess walking on (Gloranthan) Earth. She also has to fulfill commitments beyond what other initiates or rune masters have to.

Jeff Richard wrote a while ago that a capital H Hero will have transgressed against their cult, too. Ludo argues that that is the way to bring progress to the cult, with ultimately the hero cult feat/Rune spell becoming a mainstream cult spell.

Ludo asks how to play out this integration into the wider cult in a game without doing something like a three year break with some charisma rolls to convince 1D6 temples to adopt your method. Jörg suggests that this may happen in the face of cataclysm when the hero’s feat becomes crucial in averting a bad fate. With the Hero Wars basically consisting of a whole series of upcoming cataclysms, no shortage there (and no big deal if the GM adds another one). Or, as Ludo puts it, there are no Hero Wars, just min-maxing players with delusion of greatness. Austin feels called out by this.

Subcults

Subcults are a way to add a new aspect to a cult entity. One thing Ludo likes about Greek mythology is that there were many places where a special role was attached to an otherwise well known deity. There was a temple of Zeus Flyswatter (Zeus Apomyios) in a great collection of temples where all manner of animal sacrifice went on, which naturally attracted flies to the slaughter.

Jörg posits a different approach: whenever you write a new myth about a deity (or otherwise cult entity), you create a new subcult. Ludo thinks that’s the business of hero cults, but Austin points out that many hero cults are basically subcults of the existing cult of their hero. There are hero cults outside of existing cult structures, with Harrek the Berserk as a case study. Austin paraphrases Jeff Richard that Harrek gets worship for the same reason Malia does: “Oh please, Harrek, don’t come this way!”

Ludo makes Jar-eel the poster girl for the opposite way, a hero fully integrated into her deity’s cult. We discuss poster girls in the sense of Carry Fisher’s Princess Leia bondage image being worshipped by young boys in (or rather from) the seventies and eighties.

Austin really likes these distinctions to be messy and ambiguous. While some of the introductory material could be more straightforward, the ambiguity is what makes Glorantha (or mythology in general) fun to play around with. “Maybe that elephant has wings.”

Austin has the revelation that the entirety of the Gods War was just a dog toy. Ludo is sure that there was a God Learner theory supporting that, and Jörg locates that in the library of the sunk Trickster library in Slontos.

Jörg offers another distinction between hero cult and subcult – when did the myth (or introduction of the feat) happen, in God Time, or as a heroic effort within History?

Ludo fleshes this out – you can come back from the discovery of how to leap trees saying “look at me, I am awesome because now I can leap over trees, so worship me!”, or you can come back saying “I went to the God Time and met this kinsman of Orlanth called Bob who taught me to leap trees, so everybody worship Bob!” Hero cults are for egomaniacs, while subcults are founded by true devotees. Or the difference between Rune Lords and Rune Priests, as Jörg puts it.

Syncretism rears its ugly head: You encounter a deity which shares certain angles with your own, like e.g. being the cruel god at the Hill of Gold, chaining Orlanth to Shargash (or the Fronelan form Vorthan) and ultimately Zorak Zoran, possibly bringing in shared magic.

Austin gives an example of how the Death Wielder feat can do such heroic mis-identification that nonetheless can give access to powers.

Ludo takes Heler as the example – this could be the personification of the rain as a bona fide deity, or it could be just the name for Orlanth’s power to make it rain without any intrinsic contradiction. Vinga can be a daughter of Orlanth or just a female aspect of Orlanth. It compares to dedicating yourself only to part of the cult, like a Star Trek fan only ever watching the original series, and not the entirety of the franchise.

We conclude that you should not ever involve yourself with a fandom. And no, we aren’t fans, we are devoting ourselves to serious study of Glorantha. Ahem.

Jörg reminisces about dipping his own feet in Gloranthan fan-subcreation tackling the weird henotheism of Malkioni worshipping regular deities, like that Aeolian sect in Heortland. This triggers Austin to bring up his deranged scribble journal. Austin (too) spent three days rambling about Aeolian sorcery in his notes.

The Aeolians sit in southern Heortland, between Orlanthi Heortland (Hendrikiland) and God Forgot, a land of atheist sorcerers who either are Brithini or think they are, imitating their ways.

Austin’s deranged ramblings for Aeolian sorcery (which may never see the light of day any more than the picture above) have new relationships between runes, or assign elements to deities which aren’t apparent anywhere else. The premise is that the Monomyth could be very wrong and the magic still works, which is made possible by having the sorcery element which doesn’t rely on the warranty of your rune magic. Sorcery gives you the tools to jailbreak your phone, it is really good at it. Sorcery also allows you to infer and use the antithesis of a rune you mastered.

Regardless whether he will use it in publication or not, what Austin found out from this exercise is that if you don’t play with the cults but with the runes you are getting different results in your sub-creation.

Austin feels that the Monomyth as presented over-emphasizes the role of the elements, He plays through an experiment where all the Lightbringer deities are purely made up of power runes, including Orlanth.

Things get too messy to transcribe, or to count potential Nysalorean riddles.

Austin rambles about Entekos the still Air Goddess being the wife of Orlanth, challenging many magical preconceptions.

Jörg rambles about Orlanth possibly not being born a storm god but becoming the Storm King through his teenage hero journey through the Gods War.

Austin riffs on how the sorcerous ability to infer the antithesis of a power might influence a henotheist offshoot of a religion.

Jörg mentions his own first steps toying with the Aeolians.

Austin talks about approaching cults as a game tool rather than a setting feature and what would be interesting to mechanically play around with. Engizi is a case study of what Austin doesn’t like very much in the core rules book, there is little to incite a player to follow this deity.

As a counter-example, Austin cites Brian Duguid’s cult of Mee Vorala in his recent The Voralans offering on the Jonstown Compendium (Brian was our guest in episode 17, by the way) Austin could see himself as a troll mushroom farmer with access to cool alchemical toys and unexpected magics. “It is a really nice blend of inventive mythology and actual I could play this.”

Jörg points out that his tinkering with the Aeolians was accompanying his first time GMing RuneQuest in Glorantha after years of experience GMing RQ in his own settings, making actual play with the rules system a powerful motivation at the time, too.

Rune Cults

Austin’s Cult of Hrundra in To Hunt A God is an example of this.

For Austin, every fun idea doesn’t stand alone but blurs into a melange. One idea behind it was an illusion-focused knowledge god would be interesting. While Hrundra turned out not to be this, this was one of the starting points. Hrundra’s monkey shape was inspired by Thoth, the Egyptian baboon-headed god of knowledge (Besides the baboon head, Thoth is also often depicted with an Ibis head, in case you were wondering how you misremembered.) Austin has a blue statue of a baboon apparently dedicated to Thoth which gave him the notion of the blue monkeys. The actual imagery for Hrundra’s species came from howler monkeys from South America. Austin likes to take not one but maybe sixteen different influences to create a new one.

To Hunt A God was intended as the big finale of Austin’s Monster of the Month series, where he wanted to throw this big cool monster into the path of the players to deal with.

Ludo asks why Hrundra was designed as a stand-alone deity rather than like Gouger, the Ernaldan cult monster boar sent as a punisher at the start of Time. Austin basically just wanted to do it this way. Really wanting to do it is part of the fun to create things this way.

Ludo asks about pitfalls, dangers etc. to look out for. Austin remembers that writing the cult was a fairly easy exercise, as he wrote the first half of the publication in about a month. The cult was following a lot of standard structures, including Campbell’s Hero’s Journey, Eliade’s shamanism, and of course the full RuneQuest cult write-up outline originating in Cults of Prax.

Playing a campaign around Sylthy in Esrolia at the time, Austin also thought how the cult would be perceived outside of the forest it protected. In his game, the Temple of the Bones is the only such cult centre in the region for a lot of the gods of the wilds, including Yinkin who does receive associate worship in many Orlanth shrines but doesn’t have a full (minor) temple anywhere except maybe in Nochet.

Jörg asks about Kipling’s Jungle Book as an influence on the Temple of Bones with its assortment of wild deities – bear, snake, large feline, monkeys…

When thinking about Hrundra, Austin’s goal was cool fun cults, with more power than a cult of this size would really earn from a pure setting perspective. Jörg points out that this is balanced by the very hard geographical limit of the cult’s influence, but Austin just likes to make the setting more “gonzo” or “Bollywood”. Austin points to the gritty and personal style on the cover of the Starter Set while the setting also allowing over-the-top magics (like the Dragonrise image in the interior of the Starter Set).

Ludo talks about a scale in the fandom of Glorantha, with some making it a very archaeological world with everyday items like looms and farming, all the way to the completely gonzo scenarios by Sandy Petersen or Nick Brooke (The Black Spear, Crimson King). Both Austin and Jörg claim both ends of the spectrum for themselves, with Austin giving an example he read about a change in Mesopotamian plowing techniques documented in cuneiform tablets led to seeds being sown deeper into the soil, leading to greater crops, leading to population growth and a period of increased warfare.

Ludo asks how runic interactions influence Austin’s writing or design. Austin regards the Form and Element Runes as nouns and the Power Runes as verbs, and the antagonism of the Power Runes plays a greater role in his design. Austin talks about how the rune dice which allow you to roll a situative rune are great props for framing a scene. Austin reads and interprets the runes, possibly more for his deranged scribbles stage of collecting ideas than for his more structured writing process.

Austin comes back to how Hrunda has lost any connection to the initial knowledge god concept, having turned into a trickster scape-goaty thing. Austin likes how Hrunda fails to fit neatly into any of these boxes, if he did he would be too mono-mythy for Austin’s tastes.

Jörg points out that Hrunda also does this by having a significant shamanic element to his theist cult. Austin emphasizes the shamanic nature of the cult and mentions how that makes getting the support for a temple unlikely. That is why he came up with the Temple of the Bones as a joint shamanic worship site where small followings of shamans of different wild gods would help one another out as lay worshippers boosting the size of the holy place.

Jörg mentions the animal worshippers of Hrunda (the non-sentient of the bluepaws monkeys) whose attendance also boosts the site beyond normal temple restrictions.

One of the images inspiring Austin was swarms of monkeys attacking people in the streets of very urban cities in India like sea-gulls. So Austin thought to throw a bunch of monkeys into urban Esrolia, as a major pain in the butt, and some of them talk.

This worship by animals is a trick first published for the Cult of Zola Fel with its intelligent and non-intelligent fish worshippers. Austin saw that and thought this should be more widespread than just one river god in the middle of nowhere.

Austin also emphasizes that the bear (Odayla) worship at the Temple of Bones is very different from the Rathori Hsunchen ways, and has no (ancestral) relationship.

Cool Toys for Players

Ludo asks for a rather specific cool toy like e.g. turtle shell powers that a player might ask for.

Austin talks about several ways to handle this. In the case of Hrunda the cult was there first, and then the toys came up when muddling around the different stories that resulted from that. Most of his key magic is stuff Austin made up following the pattern of Yinkin (which in turn follow the pattern of the Hsunchen entities while avoiding the shapeshifting aspect).

Austin remembers thinking about writing a short cult creation guide when the Red Book of Magic first came out, but other commitments and doubts about how it would be received resulted in about ten thousand words being shelved indeterminately. Ludo suggests publishing such notes as the Conrad Library, while Jörg asks for the Akhelas manifests. If you ever see “Volume 2 – The Great Re-Ascent of Bullshit” in print, Ludo suggested it here first.

Taking the RQ2 Rune Power concept backwards, Austin posits that if you see a bunch of spells with shared runes, you can create a cult from that retrospectively.

For an example cult of Fire and Death, Austin talks about taking five or six spells, say True Spear, Produce Light, Earthwarm and maybe two or three others. One of the spells is exciting, three are okay and useful, and then there is your equivalent of Cloud Call which is mythically significant but dull as hell. You muddle these together, and then you ask what are the stories that led to those spells.

So if you have a fire god with True Spear, how did he win his spear? Was he born with it, did he tear his own rib out to get a spear, did he climb a tall mountain and use its peak as a point of his spear, did he chop a tree down and now carries a spear but his cult is hated by elves, was he born as a spear and then became a man – weird random ideas that you can draw from.

A rune spell in Austin’s mind is really an embodiment of the myth. You are throwing a story at somebody and it blows up in their face.

So if you want to have Proteus for a spirit cult, you might make it slightly malignant, to have to keep the magic you need to acquire a new form regularly (Austin initially suggested once a season, but then ruddered back to once a year). It is a way to have the really cool toys, but requiring that you cast Sanctify or similar regularly is going to cost you. Reasons to adventure, reasons to do stuff.

Hrunda has the story about stealing fruit, as a consequence initiates cannot let each other starve, and as a shaman or rune lord your are not even allowed to pay for food, you have to be offered it for free, steal it, or grow it yourself,

As a last word on creating cults: Just do it. You will make mistakes, and you will learn from these.

Austin talks about the upcoming volume on Mythology in the Cults of RuneQuest series and how he fears it might contaminate his creativity. Jorg speculates about some of the contents, with many old acquaintances appearing, and absences being more glaring than inclusions.

Closing Statements

Austin’s stuff can be found on the Jonstown Compendium. He also has a website, where he publishes his weekly blog, Glorantha stuff, backstory for his original world, a play report for Six Seasons in Sartar, a review of The Design Mechanism’s Mythic Babylon, trying soloquest rules and solo gaming, etc.

Austin’s most recent offerings on the Jonstown Compendium are the print version of To Hunt A God and the PDF of The Queen’s Star, a site-based adventure where you go to the Cinder Pits in Colymar lands, mucking around with fallen sky gods trying to convince them to let someone go.

Ludo takes the occasion to promote some of the stuff he has recently participated in on the Jonstown Compendium: Veins of Discord by Finmirage where he did most of the illustrations and the layout, a few drawings in The Voralans by Brian Duguid, the cover for To Hunt a God, and also one little illustration in The Queen’s Star. Ludo also teases Jörg about his still not upcoming work on Ludoch (and fisherfolk) in the Choralinthor Bay.

The God Learners on Holiday

On a more general note, the next episode of the podcast is scheduled for early September, so please hold the line (And that’s the last telecommunication simile in this transcript, too.)

Any delays in releasing this episode are Jörg’s fault for being late with the transcript.

62 επεισόδια

Όλα τα επεισόδια

×Καλώς ήλθατε στο Player FM!

Το FM Player σαρώνει τον ιστό για podcasts υψηλής ποιότητας για να απολαύσετε αυτή τη στιγμή. Είναι η καλύτερη εφαρμογή podcast και λειτουργεί σε Android, iPhone και στον ιστό. Εγγραφή για συγχρονισμό συνδρομών σε όλες τις συσκευές.